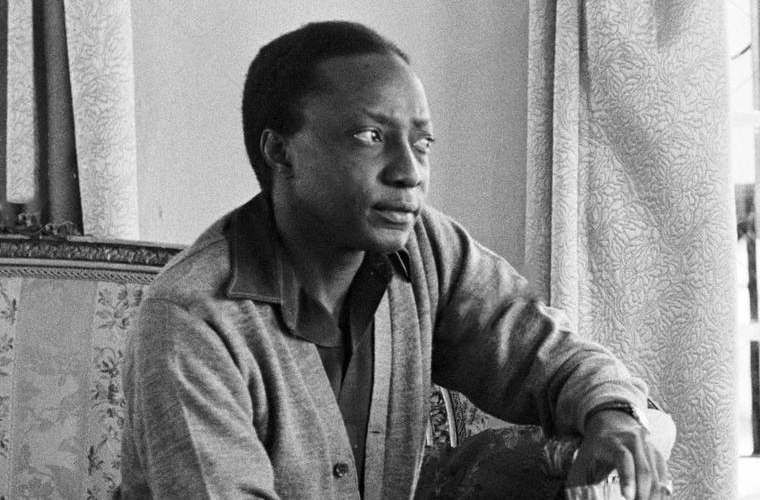

Sir Edward Mutesa II’s death on this day in 1969 remains one of Uganda’s most poignant political tragedies—an ending shaped by the bitter fallout between the Kabaka and Prime Minister Milton Obote, the 1966 crisis, and the long, cold years he spent in exile in the United Kingdom.

Mutesa had risen to national prominence not only as the traditional leader of Buganda but also as a key figure in Uganda’s early nationalism. In 1962, he became the country’s first President in the delicate UPC–Kabaka Yekka coalition that brought independence.

But the alliance was uneasy from the start, with both sides suspicious of the other’s ambitions. Tensions deepened over federal arrangements, Buganda’s demand for autonomy, and Obote’s growing centralist power.

By early 1966, a political storm was already gathering. Obote was facing accusations of corruption and constitutional overreach, while the Kabaka and Buganda Lukiiko increasingly resisted what they saw as erosion of Buganda’s rights.

Matters exploded when Obote suspended the constitution and replaced it with one that abolished federalism and stripped the Kabaka of national influence.

Then came the decisive moment: the May 1966 attack on the Lubiri. Troops commanded by Col. Idi Amin stormed the royal palace in Mengo, forcing Mutesa to flee for his life. Barefoot and disguised, he escaped through the palace’s back gate under gunfire, beginning a harrowing journey that took him through Tanzania and eventually to London—an exile marked by isolation, financial struggle, and declining health.

It was in London that he lived his final years, cut off from the kingdom he once led. Reports indicate he struggled with deep loneliness and poverty, living in a small flat in Camden Town. On November 21, 1969, Mutesa was found dead.

Mutesa, was discovered dead by his bodyguard Capt Jehoash Katende who by norm would have to leave/or return to the house by kneeling and greeting the Kabaka aloud. On this specific day, he returned from work and knelt to greet the Kabaka, but his pleasantries got lost within the walls of the small condominium he shared with the royal.

There was neither answer nor attempt for the same. Katende approached his King to ascertain if all was well, he was gone. Mutesa’s 63 kilograms of body weight and 5.6 feet of height lay there staring at him, lifeless.

Mutesa and Katende had spent three years and six months in exile, living on crumbs from the former’s friends, completely neglected by Britain which was once Mutesa’s ally, and seriously loathed by Obote’s government back home.

The monarch and nationalist had died hours after celebrating his 45th birthday.Dr Arthur Gordon Davies, a surgeon who conducted the post-mortem on behalf of the British government also concluded thus; “I find that the deceased died on the 21st day of November 1969 at 28 Orchard House, Rotherhithe, from acute alcohol poisoning.”

The official account stated he succumbed to alcohol poisoning, but many Ugandans have long suspected foul play, pointing to political tensions and the Motive Obote’s government may have had in silencing a popular royal figure.

Nothing was ever proven, but the doubts have persisted for decades.

Mutesa’s burial in London’s Kensal Green Cemetery was a subdued affair, far removed from the grandeur of Buganda royal tradition. For years, the kingdom and his supporters yearned for his return, but the political climate in Uganda made it impossible.

Only after Idi Amin overthrew Obote in 1971 did the opportunity arise. In 1972, the Amin government authorised the repatriation of the Kabaka’s remains, a move that was both politically symbolic and deeply emotional for Buganda.

When the body was flown back to Uganda, thousands lined the roads from Entebbe to Kampala in an extraordinary outpouring of grief and reverence. The reburial at Kasubi Tombs followed full cultural rites, restoring the dignity that exile had taken away.

It marked not only the physical homecoming of a king but also a moment of reconciliation between Buganda’s wounded identity and its turbulent political past.

Today, Mutesa II is remembered not merely for the monarchy he embodied but for what his life and death came to represent—the fragility of Uganda’s early statehood, the dangers of political intolerance, and the enduring resilience of a people whose history refused to let him fade into exile.