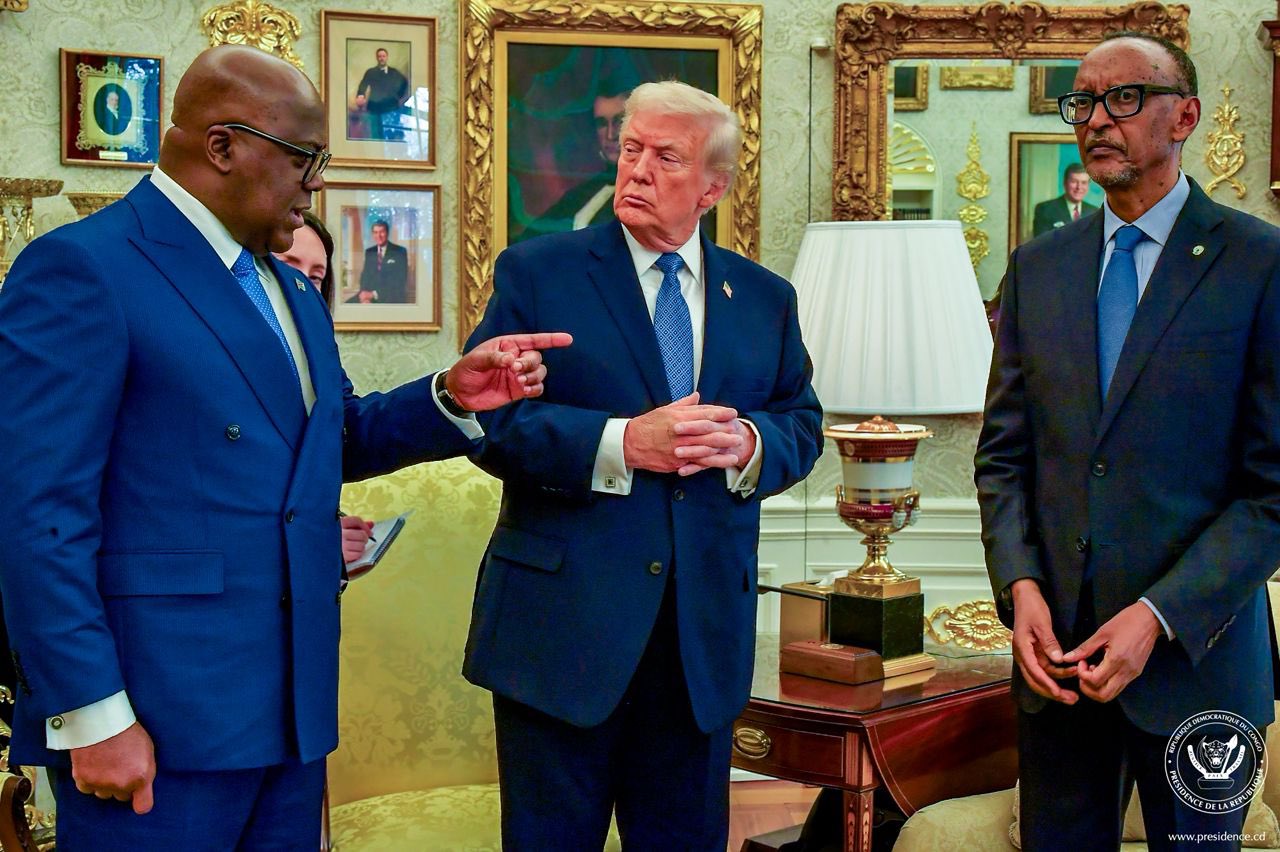

A peace agreement signed between the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda in Washington has sparked sharp criticism from regional politicians, analysts and security experts, who say the deal appears to serve US interests more than those of the two rival nations.

US President Donald Trump hailed the pact — now widely referred to as the Washington Accord — as a “landmark” step toward ending decades of bloodshed in eastern DR Congo.

He said the deal would “settle the hearts of suffering refugees” and restore stability to one of Africa’s most volatile regions that have witnessed bloodshed for over three decades.

But experts argue the accord offers only temporary calm and exposes deeper failures within African regional blocs tasked with resolving conflicts on the continent.

Prof Solomon Asiimwe, a security expert, told Nile Post reporters the deal is “a double-edged sword,” warning it may deliver “it is a big diplomatic shift” during the Trump era while entrenching long-term geopolitical imbalances.

"The accord is a good move but shall depend on the implementation mechanisms just if the two leaders commit to it," Asiimwe highlighted.

Analyst Rodgers Barigayomwe echoed the concerns, saying the agreement reads like a vote of no confidence in EAC and shows lack of Pan African spirit," that leaves Washington with strategic leverage over both Kigali and Kinshasa.

A key point of contention is the economic dimension. Critics say the US stands to gain unprecedented access to rare minerals in both countries — a sector central to America’s growing demand for cobalt, lithium, manganese, tantalum and copper.

Earlier briefings from the US Department of State estimated DR Congo alone holds mineral reserves worth more than $25tn, vital for producing electronics, electric vehicles, renewable energy systems and military hardware.

“The economic implications could be positive regional autonomy, as East African community integration may emerge stronger,” Prof Asiimwe hoped.

The agreement also highlights ongoing security grievances. Kinshasa has long accused Rwanda of backing the M23 rebel group, which controls parts of eastern DR Congo.

Kigali, in turn, demands the DRC dismantle the FDLR — a militia that includes remnants of the group responsible for the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

Politicians in the region say the Washington signing underscores the diminishing influence of African-led mediation efforts, leaving the future of the accord uncertain.

The key question now: How long can this deal hold — and at what cost?