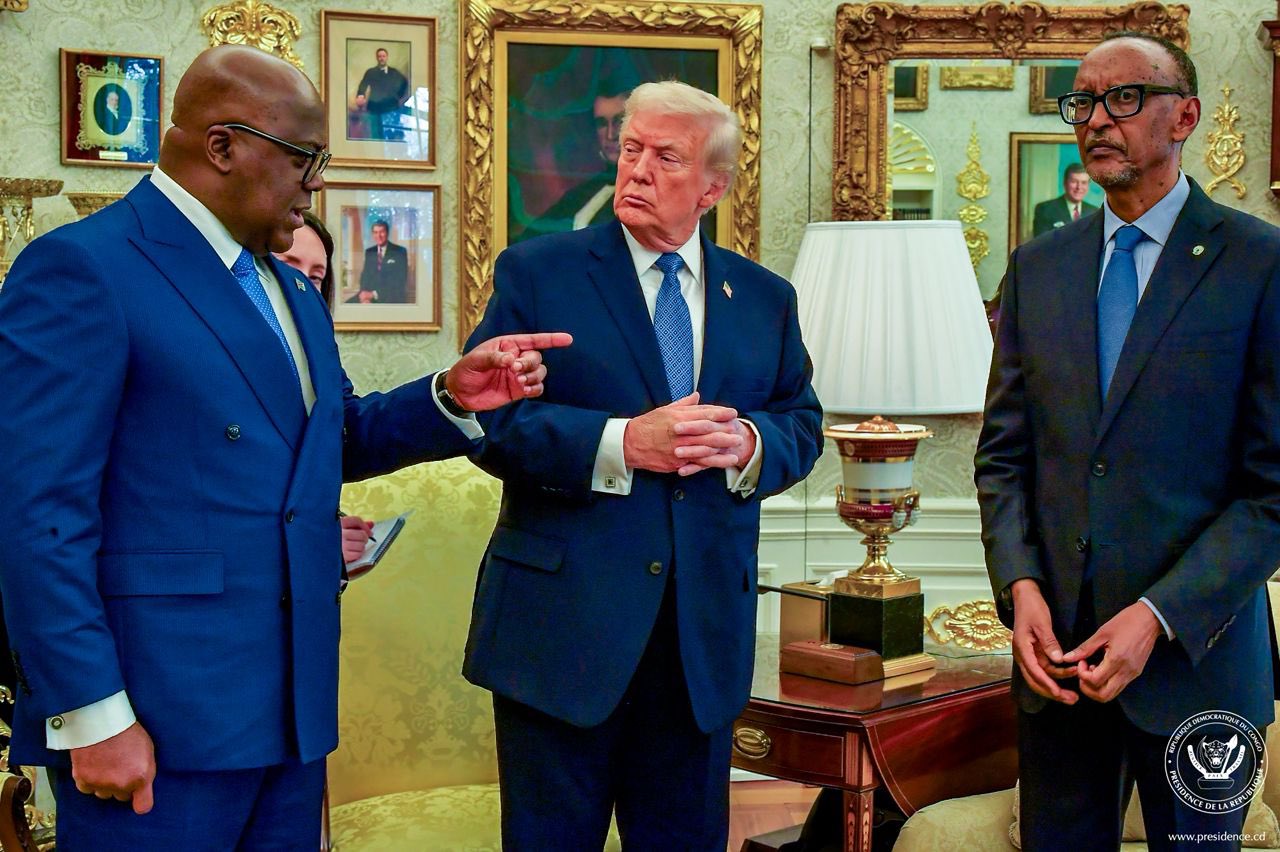

There were so many awkward moments inside the Donald J. Trump Institute of Peace building in Washington, DC, on Thursday, December 4, where US President Donald Trump had brought together Presidents Paul Kagame of Rwanda and Felix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

But two stood out.

First, the seating arrangement was bizarre. White House officials placed Trump on the far right of the table, Kagame in the middle, and Tshisekedi on the left. For a mediator, the natural position would have been in the middle—between the two leaders whose countries have spent decades locked in mutual suspicion and, at times, open conflict.

Now, when the time came to shake hands for the cameras, from his position Trump naturally met Kagame first, then to Tshisekedi.

Kagame did not turn fully to face his counterparts, an almost imperceptible gesture loaded with historical weight, signalling reluctance—or perhaps contempt.

Then came the clincher. Tshisekedi handed his copy of the agreement to a White House aide rather than directly to Kagame sat just inches from him. This was not a misstep; it was a calculated act, a subtle display of the deep mistrust that has defined Rwanda-DR Congo relations for decades.

Trump, of course, spun the scene as a historic triumph. “These two gentlemen… liked each other after I spent time with them,” he said. “They had spent a lot of time killing each other, and now they’re going to spend a lot of time hugging and holding hands.”

Scattered laughter greeted his remarks, but for anyone familiar with the region’s history, the claim was laughable.

The “Washington Accords,” as Trump’s White House called it, is the latest in a string of high-profile yet hollow diplomatic exercises aimed at pacifying the US president’s appetite for dramatic foreign policy wins.

On the ground in eastern DR Congo, the reality is far more brutal.

As the spectacle unfolded in Washington, Congolese government forces, backed by allies from Burundi and local militias, were clashing with the M23 rebel group in Kamanyola, South Kivu. Three days before the Trump-led summit, fighting had intensified.

Just this morning, Friday, December 5, M23 reported that Kinshasa had launched “relentless attacks against densely populated areas in North and South Kivu, using fighter jets, drones, and heavy artillery.”

Two bombs struck the Rubumba neighborhood, killing four civilians and seriously injuring two others.

The M23 were not invited to Washington. And this is the core flaw of the accord: it attempts to resolve a conflict without including the primary belligerent - never mind that the conclusion is that Kagame is the one man who can say stop and Corneille Nangaa will ask his military commander General Sultan Makenga to heed.

Over the past decade, numerous regional and international initiatives—from the Luanda Accord mediated by Angola, to East African diplomatic efforts, to the Doha agreement in March 2025—have struggled to get all parties to commit meaningfully.

At the Doha meeting hosted by Qatar’s Emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, Tshisekedi and Kagame were finally brought together. Even then, Tshisekedi, who in 2023 compared Kagame to Hitler and swore he would only meet him in heaven or hell, publicly swallowed his words—but the gesture was superficial.

Ceasefires agreed at Doha never took hold. The M23, who first captured Goma in November 2012 before regional pressure forced a withdrawal ten days later, are different.

After the second advance and capture of Goma in January this year, their territorial ambitions are far broader, encompassing parts of South Kivu and establishing parallel administrations. They claim to be restoring social and economic infrastructure, and are reportedly generating over $1 billion per month in mineral revenue.

Can a rebel movement that has invested in local infrastructure simply reverse course because of a piece of paper signed in Washington? Tshisekedi knows that is not going to happen. His government vows to “never surrender even a piece of soil” to what it views as Rwandan proxies.

Unless Trump made him abandon such thought - which is unlikely - the Washington signing does not translate into concessions on the battlefield for Tshisekedi—it is an exercise in optics, not authority.

Trump, naturally, spun the narrative differently. “It’s going to be a great miracle,” he told reporters, claiming that the leaders would “prove” themselves and deliver immediate results.

Such rhetoric ignores the entrenched realities of eastern Congo, where decades of conflict, resource exploitation, and regional power dynamics make any quick resolution impossible.

Long-standing issues

Historical context underscores the fragility of Trump’s claims. The conflict between Rwanda and DR Congo dates back to the 1994 Genocide of 1994 against the Tutsi, which killed over a million people and triggered massive cross-border flows of refugees and armed militias.

After Kagame led his Rwandese Patriotic Front forces to stop the pogrom, the militia responsibility for the slaughter, the FDLR, fled westwards into DR Congo jungles where they have entrenched themselves and joined forced with the government forces known by its French acronym, Fardc.

In Kigali, the acceptance of the FDLR militia in the Fardc ranks is an extension of the genocidal ideology and the Kagame regime has always claimed that the same elements keep infiltrating the borders to maim and kill citizens.

Rwanda’s involvement in the subsequent wars of 1996 and 2003 in DR Congo's Kisangani region further entrenched mistrust. Kagame has ruled Rwanda since 2000, overseeing a tightly controlled and economically dynamic state, while Tshisekedi assumed the presidency of DR Congo in 2018, inheriting a fractured state with limited capacity to project authority into its eastern provinces.

The Washington Accords attempts to paper over these deep fractures with promises of “expanded economic cooperation” and “peaceful engagement,” but fails to address the core problem: the M23 and allied militias are not in Washington. They are in Congo. They control territory. They control revenue streams. They have no incentive to negotiate on terms dictated by outsiders.

Even the optics of the ceremony betrayed the fragility of the accord. Tshisekedi’s refusal to hand his signed copy to Kagame and smile at him, and Kagame’s stiff posture reflect decades of historical grievances, while Trump’s mispronunciation of both leaders’ names and his jocular references to “killing each other” reduced a life-and-death conflict into a punchline.

Trump cracked several jokes, some funny, some bizarre and Kagame did join the audience in laughing and clapping. But Tshisekedi sat glumly like what was happening was forced on him.

The spectacle was less about diplomacy than about reaffirming Trump’s image as a dealmaker—a president who “ends wars” by simply hosting photo opportunities.

Meanwhile, reports from the DR Congo tell a different story: over 7,000 people killed and 450,000 displaced in 2025 alone, as M23 rebels consolidate control over eastern territories rich in minerals. Any “miracle” Trump predicted will not materialize unless the accord addresses the structural causes of the conflict: historical grievances, ethnic tensions, economic incentives, and regional rivalries.

For all the rhetoric, the Washington Accords mirrors past failures. The Luanda Accord and Doha agreements achieved nothing substantial on the ground. Kagame and Tshisekedi can shake hands and smile for photos, but unless M23 is brought to the table and the Congolese state asserts meaningful control over its eastern provinces, the fighting will continue, and civilians will continue to suffer.

After all these, picture Kagame's most avid stance on African issues. The Rwandan leader, like his mentor Yoweri Museveni, has always argued that African crises should be resolved by Africans. As Kagame put it during a peace and security forum in Dakar: “If we allow others to define our problems and take responsibility for solving them, we have ourselves to blame.”

More recently, at the inaugural International Security Conference on Africa (ISCA), he reiterated that “Africa’s future, particularly in matters of peace and security, cannot be outsourced.”

He has not walked back on this ethos and it is hard to see the Washington Accords turning into the whitewash that erases Kagame's fond principle. Even if even African solutions have failed before.

On Tuesday, July 30, 2002, and then DR Congo President Joseph Kabila and Kagame signed a peace agreement in Pretoria, South Africa, aimed at putting an end to the war.

The agreement, under the mediation of then South African President Thabo Mbeki, stated thus: "The DR Congo will disarm the Rwandan Hutu militia (former Rwandan Armed Forces, FAR, and Interahamwe) on its territory, and then Rwanda will agree to withdraw its troops."

Little has been revealed on what the parties agreed on in Washington on Thursday but if it is anything close to what Mbeki had Kinshasa and Kigali pretend to agree to, it must be another repeat of the same.

In the end, Washington on December 4 was a theatre of optics and ego. Trump could claim another foreign policy triumph. Kagame and Tshisekedi could publicly pledge cooperation. But for those living under the shadow of M23 in South Kivu and North Kivu, this is little more than a hollow ceremony, a farce disguised as diplomacy.

History suggests caution. Eastern Congo has survived and perished under multiple peace accords that failed to account for local realities. Without including all stakeholders, including rebel groups and civil society, and without addressing underlying grievances and resource-driven incentives, any agreement signed hundreds of miles away will remain just that: paper, not peace.

The Washington Accords is glossy, performative, and designed for cameras. On the ground, the war rages on, civilians die, and Trump’s claim of a “miracle” remains wishful thinking. In the grand theatre of international politics, sometimes the loudest applause masks the emptiest outcome.