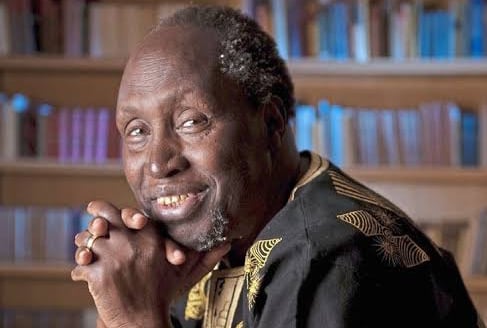

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Kenya’s most celebrated literary figure and one of Africa’s most influential writers, has died at the age of 87 in California, US,following complications related to kidney failure.

His daughter, Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ, announced his passing on May 28, 2025, through a heartfelt Facebook post.

She wrote: “It is with a heavy heart that we announce the passing of our dad, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o this Wednesday morning, 28th May 2025. He lived a full life, fought a good fight. As was his last wish, let's celebrate his life and his work. Rîa ratha na rîa thŭa. Tŭrî aira!”

She said the family’s spokesperson, Nducu wa Ngũgĩ, would provide details about his celebration of life in due course.

The renowned author, born James Ngugi in Kamiriithu, Kiambu County in 1938, had been undergoing dialysis thrice a week and receiving care at his home in Irvine, United States.

He had also undergone surgery in recent years as his health deteriorated.

Ngũgĩ’s literary career began in the 1960s, and he quickly rose to international prominence with Weep Not, Child (1964), the first English-language novel published by an East African.

He followed this with The River Between, A Grain of Wheat, and Petals of Blood — searing indictments of colonialism and the betrayals of post-independence leadership in Kenya.

Fermented at Makerere

Ngũgĩ arrived at Makerere University College - as the university was called then - in 1959, joining a generation of young African thinkers eager to define the post-colonial future through literature and political engagement.

It was here, while studying English, that he began to find his voice as a writer. His first major work, The Black Hermit, was staged at Uganda’s National Theatre in 1962 during the country's independence celebrations, marking his formal debut as a dramatist.

It is also widely believed he wrote - or at least started writing - his first novel, Weep Not, Child, while a student at Makerere.

In his memoir Birth of a Dream Weaver, Ngũgĩ vividly recalls the intellectual ferment of Makerere in the early 1960s, where ideas about nationalism, identity, and language sparked long conversations and lasting convictions.

Ngugi returned to Makerere in 1969 as a Creative Writing Fellow, this time as a mentor and established author.

His presence contributed to a growing literary culture at the university, where he worked with aspiring writers and continued developing his political and artistic vision.

This period, marked by growing political unrest in the region, sharpened his sense of literature’s power as a tool for resistance and self-definition.

Makerere offered Ngũgĩ both the freedom to explore and the tension to question, making it a crucible for many of the ideas he would later express in works such as Petals of Blood and Decolonising the Mind.

A committed decolonial thinker, Ngũgĩ turned away from writing in English and began producing novels, plays, and essays in his native Gikuyu, asserting that language was central to cultural liberation.

His 1986 book, Decolonising the Mind, became a manifesto for writers seeking to unshackle African literature from colonial frameworks.

He was imprisoned without trial in 1977 by the Moi regime after staging the politically charged play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want) in Gikuyu.

While in detention, he wrote Devil on the Cross on prison toilet paper — a defiant work of satire against neocolonial greed and corruption.

Following his release and subsequent exile, Ngũgĩ held academic positions in Britain and the United States, including at Yale University and the University of California, Irvine.

He published widely in both fiction and critical theory, including the Wizard of the Crow (2006), a sprawling novel set in the fictional Free Republic of Aburĩria, and the memoirs Dreams in a Time of War, In the House of the Interpreter, and Birth of a Dream Weaver.

Ngũgĩ was frequently mentioned among contenders for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and although he never received it, his global influence was unquestioned.

His later works continued to interrogate the relationship between language, memory, and political imagination.

Most of Ngugi's literary works have been staples in Uganda literature syllabi with Weep Not Child, A Grain of Wheat, Petals of Blood, and the River Between all alternating across in both ordinary and advanced levels of high school.

Tributes have poured in from across the world, hailing him as a literary revolutionary, a political dissenter, and a teacher whose writings helped generations confront their histories.

He is survived by several children, including authors Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ and Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ.

Further details about funeral arrangements will be communicated by the family in due course.