Analysis: Why the opposition cannot find space in Uganda

Last month parliamentarians in Uganda came to blows over a private members bill that proposed removing age limits from the 1995 Constitution.

By removing the upper age limit of 75 (the proposal will also remove the lower age limit) MP’s from the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) are paving the way for President Museveni to extend his three decades in power.

Keep Reading

Although Museveni has been careful to distance himself from the proposed amendments, it is clear that he is orchestrating the process behind the scenes: just as he did in 2005 when term limits were removed from Uganda’s constitution.

If the fracas in parliament looked as though it was a fair fight, it was only because Uganda’s parliament has just 52 seats.

Construction of a new building began in 2016 in recognition of the need to better house the 426 MPs in the country: a number that has increased by 150 since 1996: an effort to reflect Uganda’s demographic growth but also to expand patronage networks.

The main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), has just 36 seats in Uganda’s 10th parliament.

Even with a handful of representatives from smaller opposition parties and 11 NRM MPs, who have come out against the bill, they fall well short of the numbers required to make any impact on proceedings in the chamber.

The NRM dominates the legislature – with many “independents” in reality NRM-leaning – holding the two-thirds majority required for constitutional amendments.

In Uganda’s multiparty elections since 2006 the FDC’s presidential flagbearer – on all three occasions Kizza Besigye – has averaged 33% of the vote, but the party has been unable to replicate his success securing 37, 34 and 36 seats: an equivalent average of 9.7% of the total seats in the respective parliaments.

FDC shortcomings

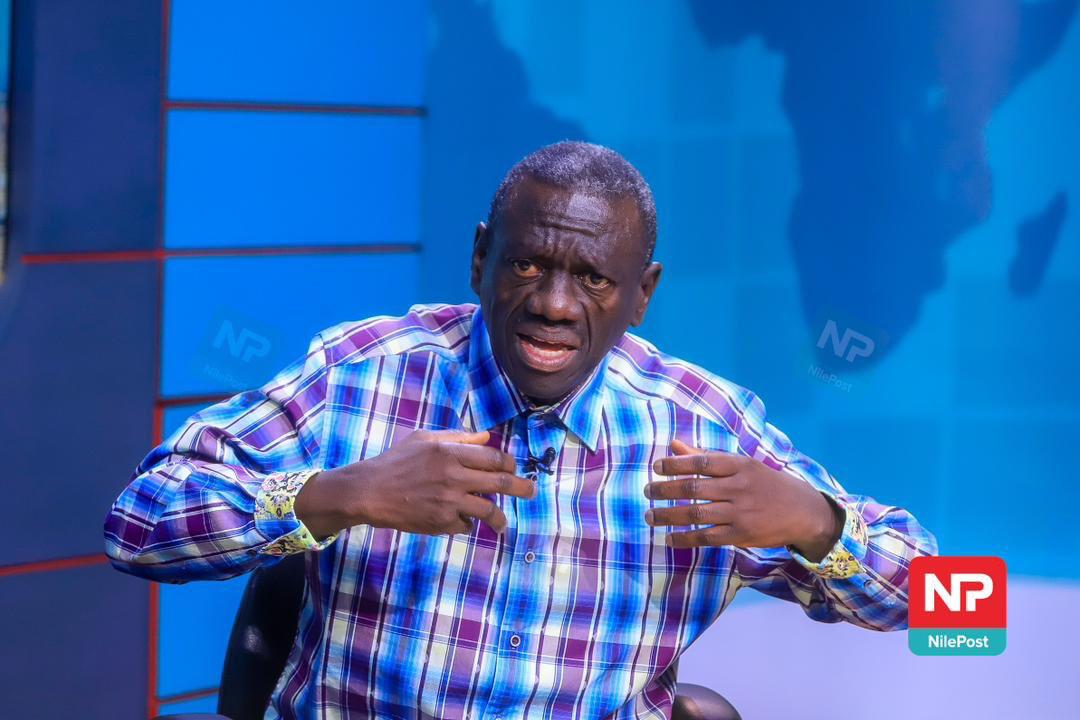

FDC party president Mugisha Muntu

FDC party president Mugisha Muntu

The FDC – unlike the Democratic Party and Uganda People’s Congress – is a fairly recent addition to Uganda’s political space.

Established in 2004 it has become synonymous with founder Kizza Besigye – to the extent that he is frequently referred to as its leader in media reporting – despite the party having been led by Mugisha Muntu since 2012.

Muntu’s approach, aimed at building grassroots party structures between elections, has juxtaposed with Besigye’s increasing push for civic activism and popular protest as the way forward.

“Divisions [within the FDC] between the ‘organisers’ [behind Muntu] and the ‘activists’ [behind Besigye] have slowed down both processes” says Eloise Bertrand a PhD researcher studying opposition parties in Uganda.

On the 2016 election campaign trail Besigye was able to tap into grassroots political support across the country – raising UGX100 million (US$27,000) for his campaign from individual donations. Although a small amount the fact the Besigye was being given gifts rather than handing them out was symbolically important.

However, the party has not shown any signs, willingness or ability to channel this support in a more structured way. Kitatta contends that “the FDC has failed to prepare well for elections. Once an election is concluded they wait until the next election cycle to start, before preparations begin”.

Uganda’s opposition parties’ failure to agree on a presidential candidate to lead the nationwide coalition – The Democratic Alliance – or to avoid competing with each other for parliamentary seats is emblematic of this lack of politically strategic thinking.

In some constituencies two candidates from different opposition parties split the vote, allowing the NRM candidate to emerge victorious; in over 50 constituencies no opposition candidates stood, allowing the NRM representative to be elected unopposed.

Barriers to entry

The FDC operates in a very challenging political space; one in which the state and ruling party are often indivisible. The cost of running a single parliamentary campaign is about Shs 60 million.

Meaning that before campaigning begun they would have had to outlay over Shs 2 billion, just to have a candidate contest each seat.

Without the state coffers at their disposal, and with supporters and business owners aware of the cost implications of openly supporting the FDC during the campaign, the cost of politics is unaffordable.

A 2016 report by the Alliance for Campaign Finance Monitoring found that the NRM was responsible for 76% of the campaign expenditure in the 16 districts surveyed.

In addition to financial barriers, the legacy of Uganda’s ‘movement system’ is another impediment to building grassroots support.

Dissent at the local level – Uganda has a five tier local council system – exists but the majority of citizens see the resolution to problems as happening within, not outside, the NRM.

According to Vokes and Wilkins “the true strength of the NRM today is not that it is rigid and powerful enough to control the dynamics of local politics, but is flexible enough to absorb them”.

Furthermore political space is at a premium.

Equitable access to the media and local radio stations was not a feature of the 2016 election campaign.

Legal provisions, coupled with the strong arm tactics of Uganda’s security services also make it difficult to engage the population in urban areas like Kampala; one of the FDC’s key political support bases.

The Public Order Management Act (2013) is frequently cited to stop gatherings of three or more people in a public place. For those who to choose to ignore the legislation the police have been quick to clamp down.

The threat of violence remains a real and omnipresent one. Whilst the FDC could have done better in recent years to improve its grassroots structures, it is also important to recognise that this environment makes it hard to achieve.

A party in name; a protest movement in reality

The FDC has increasingly looked to instigate and lead public agitations, seeing it as a more, or at least equally, effective tool of opposition.

The 2011 ‘walk to work’ protests were successful in temporarily destabilising the regime but subsequent efforts to replicate its success have failed to generate the same level of support.

And protests remain an urban phenomenon; the NRMs rural base remains relatively untouched.

The FDC can also argue that whilst Uganda’s parliament is often a place of vibrant debate and discussion, the institution can be, and has been, railroaded by the executive.

Bertrand believes that “any change of power in Uganda is more likely to come from a collapse of the NRM”, perhaps as it seeks to transition in the post-Museveni era.

But that departure does not appear to be likely in the short-term as the orchestrated removal of age limits looks as though it will succeed, despite vigorous opposition, once the NRMs parliamentary numerical advantage asserts itself.

For the FDC perhaps the answer lies with Uganda’s youth. About 45% of the eligible voters in the 2016 elections were not born when Museveni came to power in 1986; a generational shift could also mark a political one.

Jamie Hitchen is a researcher at Africa Research Institute. The views expressed here are his own.