The Face of an Abortion Debate

Rachael was 11 when something moved in her tummy, she is now 14, out of school, without a home and away from a debate that concerns her deeply.

There was a tear darting down her brown face, searching, in earnest for a ground to fall on. Not the hard cemented one where her feet webbed each other this afternoon but the one it fell on that evening.

Her father’s living room floor.

Rachael [Not her real name] knew her vowels by heart and recited them carefully.

Learning came hard on the dingy school benches of Kireka, a suburb of the city.

It often involved paused stares at a rickety train locomotive pulling through the makeshift iron-sheet shops and homes of third rate traders, or if not, it took the shape of classless afternoons at the school football pitch, an undeveloped dirt-red swamp structure where the ruins and empty dreams of a world-class hospital were buried.

Kireka was the home of football dreams. On the laps of it’s washed down, people was mothered the nation’s biggest football stadium. It sat round and heavy, elegant and stoic imposing over the bustling ghettos and sugarcane plantations.

From Rachael’s home, it’s initials ‘Mandela National Stadium’ caught her morning gaze, long and hard. Even at this pitch, the dirt brown one with surprise pops of green grass, it was easily visible.

“He gave me a chance to play with the boys” Rachael started her answer to my question on how they’d met.

“He was a good football coach, among the best here”

Rachael wore a face of fear, embroidered on its hems by silence. Her pinky finger twitched endlessly every time she spoke. Shy was her permanent residence. An address, this coach she admired had confined her to.

I’d met Rachael through a web of friends strung together by endless phone calls.

The first, to Winnie, a longtime friend who worked in the budding industry of non-profits preaching sex-education in the country.

Her office occupied an acre piece of land in prime Bukoto where oligarchs and old money dons resided. Many of the homes here were swallowing in the pit of office space. It partly explained why, when we tried finding it that Monday morning, we’d looked from gate to gate for a signpost of ‘Uganda Young Adolescents Health Forum’.

A manicured compound held back the green molds that populated the wall which made a fence. The house had been partitioned; the living room, where guests arrived to turned into a reception, the master bedroom, an office for the executive director and the garage, where we would set up our cameras, a boardroom.

Rachael hadn’t arrived when we got there but Winnie kept us in good conversation. Joshua, the videographer was tilting lights in the room hoping to create the perfect blur shot.

A month before this day, I’d been leafing through a document from the Ministry of Health I’d been sent. The email it came with was careful to label it, ’For Your Investigation Consideration’. Deep in the pages, a fact glossed over, had caught my eye.

“800 abortions” “That can’t be true,” my editor remarked when I first told her.

“800 abortions daily” I reiterated.

In that moment, the one where we asked ourselves whether it was true, the story would be approved. Over weeks of research, the number became more believable. The sexual debut age had more than halved in a decade to 12 years.

Rachael had clocked in at 11, a year less. And through a rape.

“He held a knife to my stomach and told me if I scream, he’ll pierce me” Rachael continued her story.

Her football coach, on one of the classless evenings, had asked Rachael to stay behind and train a little more. She admired the boys who played well. They’d travel to many countries to showcase their talent and Rachael wanted that too, although, she also wished, if money would allow an education, to be a surgeon.

A month after that incident, Rachael excused herself from a mid-morning class feeling wobbly. She dashed for the mud and wattle pit latrine that neighbored her school and let out a pouring of her breakfast.

“At first I thought it was malaria,” she told us. “But then the vomiting was recurring”.

She was pregnant. A month and two weeks in.

*********************

2

87% of Ugandans belong to atleast three religions Catholics, Muslims or Anglicans. They believe everything the church tells them about abortion but the numbers on early sex and teenage pregnancies, or even pregnancy outside marriage betrays the faithful’s cling onto religion in the abortion debate.

“If you’re pregnant, you should have it” Sheikh Juma authoritatively stated.

He was slouching back into a black sofa, with Qurans lined up behind him. His office, on the side quarters of the Gaddafi Mosque doubled as the sex information office for young muslims.

Every month, he saw the numbers trekking into his office reduce. From hundreds to tens and now, even five were a good catch.

“Young men, you find them in bars, in disco halls” he lamented.

Sheikh Juma’s sentiment was relatable for many religions.

Uganda is a secular state, atleast in name. In numbers though, over 87% of the population belong to a religion. The three dominant religions; Catholics, Anglicans, and Moslems in that order do not permit abortions – much less sex before marriage.

But politicians fear crossing them. They hold power – over both moral conscience and political futures. It partly explains why, the Ugandan constitution still maintains article 22, particularly its second sub-section that prohibits abortions, even in circumstances of rape, incest or defilement.

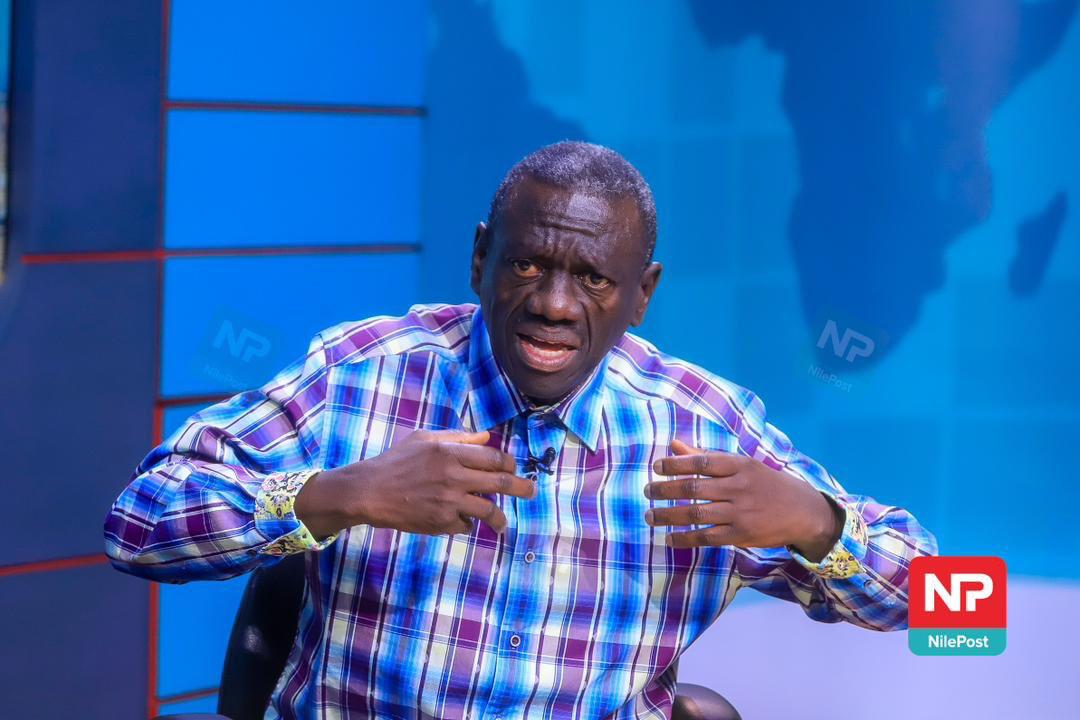

“There have been sections of civil society that have asked us to broaden that section,” says Junior health minister Sarah Opendi

“But every time we try, people come up and raise red-flags, we have been forced to withdraw even the guidelines”

In 2016, during an election year, the ministry of health had released a raft of guidelines. Part of them included allowing abortions for rape, defilement, and incest cases.

A day after they were suggested, on a lectern at the Imperial Royale Hotel, he thumbed down his index finger, adjusting a round pink cap on his head first, reading with careful emphasis Archbishop Cyprian Lwanga, the leader of the Catholic church in Uganda said;

“We recommend the withdraw of the abortion legislation” he paused, “In its entirety” as he breathed down heavy.

The ‘we’ in his statement, was, of course, the Interreligious council, a motley of religious groups in the country. They constituted the most powerful joint lobby for religious interests.

He was making no mistake on who should receive his message that when he paused again, he took a long glance at the Speaker Of Parliament, Rebecca Kadaga who shifted a bit in her seat.

In the following weeks, parliament put to their dusty shelves the regulations, and with them, the dreams of many young girls.

A year on, Kadaga herself was announced by the religious body as the face of ‘Uganda ProLife Parliamentary Caucus’ a lobby group for tightening abortion restrictions to ‘protect the family’.

*********************

3

Abortions, in Kampala, cost as little as 160,000shs but the cheaper they are the more dangerous and unsafe they are.

The first time she walked up to the doctor, Rachael knew of two likely occurrences – death or recurring bleeding. Her brother, a muslim, had briefed her when she confided in him. “You can’t bring shame to the family” she recalls him saying. He forked out 100,000 shillings and directed her to a doctor for an abortion.

“The process was very painful” she remembers.

The term health activists use to describe what she went through was ‘induced abortion’. Doctors, however, call it dilation and evacuation. It involves softening the cervix and later using suction tools to remove the tissues formed inside the body.

Typically, it is mostly carried out in the first trimester of pregnancy, the first thirteen weeks.

Some girls, unluckier than Rachael, use local herbs that terminate the pregnancy by bleeding out the tissues.

“An old lady on the village gave me the herbs, I bled for almost two months,” another girl told us in one of the interviews.

The Guttmacher institute that polls abortions notes that they account for 13% of maternal deaths globally, but in Uganda specifically, they led to 1500 deaths annually.

This figure is routinely repeated at the Reach A Hand Uganda [RAHU] offices, a local health advocacy group.

“It is about access to information” Hellen Amutuhaire, RAHU’s Program officer says. “Young people are making decisions on when to have sex, and what to do when they get pregnant and yet they don’t have information” she adds.

The raft of regulations, largely campaigned for by these pro-choice groups, had been shelved in parliament and branded a campaign to teach homosexuality in schools.

Girls like Rachael, RAHU insists, were the intended beneficiaries of the regulations. RAHU argues many young people’s dreams are stifled by bad decisions made by lack of access to sexual and reproductive health information.

“I was always studying to be a surgeon” Rachael sobbed.

She was now two years out of school, beaten down by the rigors of life, and dancing to put food on the table.

The kind of abortion she had gotten, considered illegal by the government, was still very much happening. Using an undercover team, we’d filmed three different attempts at which doctors were willing to carry it out, albeit in secrecy. The amount was now up to 160,000 Uganda shillings and it took about three hours to conduct, clinic attendants told us.

All of Uganda’s 345 health centers are equipped to carry out abortions – though it's only a reserve for circumstances where the mother’s life is in danger. Hypocritically though, all of them offer post-abortion care services for unsafe abortions. Government forks out 37 billion shillings to treat post-abortion complications.

At the ministry of health headquarters, four floors up in the deep end of a corridor where the door labeled ‘State Minister’ opened for a deep blue carpet and brown office furniture, Sarah Opendi swung in her black leather chair curbed with brown wood on its edges.

“We are simply burying our heads in the sand” she concluded our interview.