As Uganda braces for the 2026 general elections, the financial divide between the ruling party and the opposition is becoming increasingly clear — and costly.

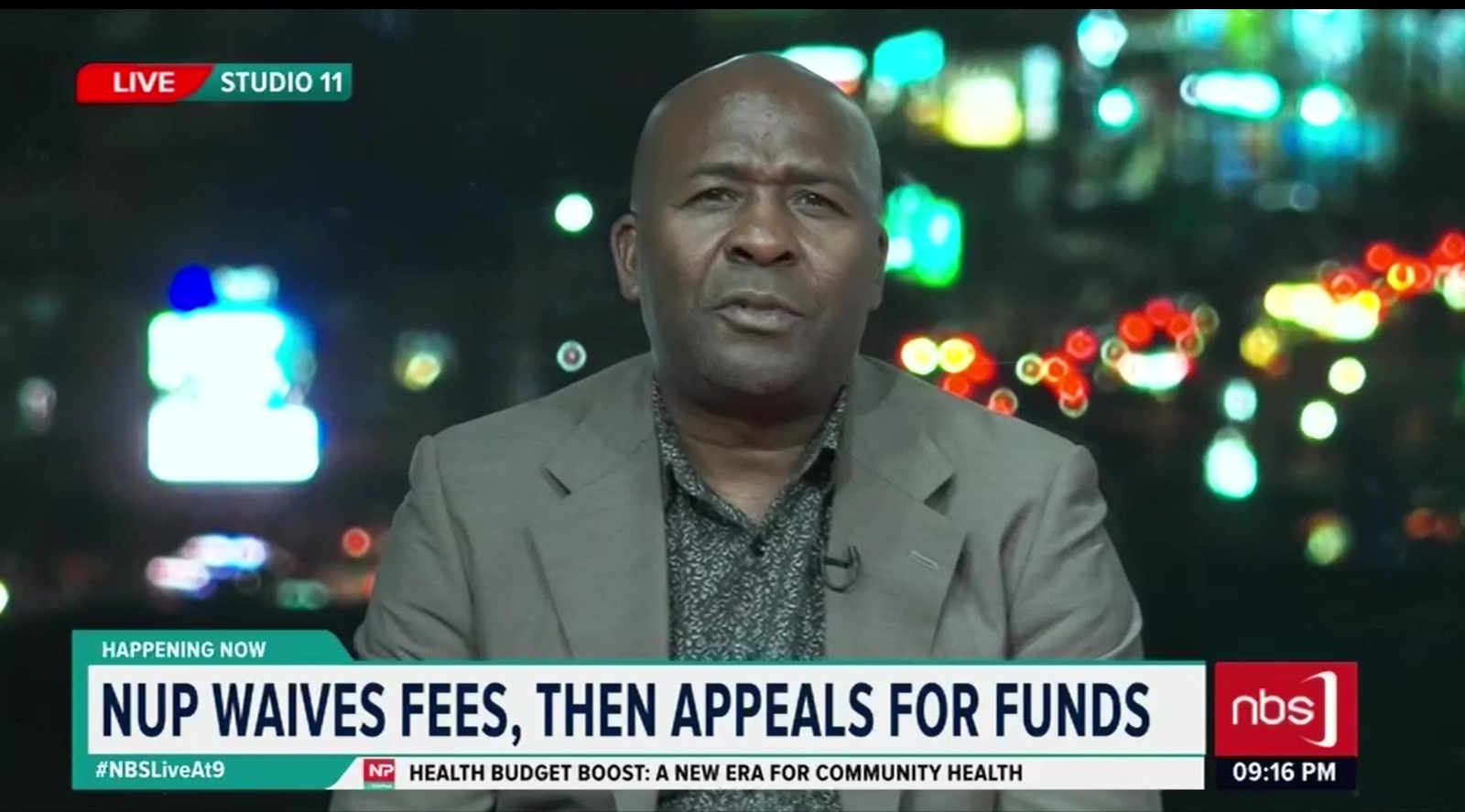

According to Henry Muguzi, Executive Director of the Alliance for Finance Monitoring, political financing is now a battleground where opposition parties like the National Unity Platform (NUP) are struggling to keep pace with the well-oiled machinery of the National Resistance Movement (NRM).

“The NRM seems to have everything aligned in its favor,” says Muguzi.

“They have a broad support base, including corporate organizations that are more than willing to bankroll them.”

In contrast, opposition parties are operating under immense pressure. For private companies or civil servants, publicly backing opposition candidates can result in repercussions, including political retaliation.

This climate of fear has left opposition parties with a narrow pool of resources and limited access to mainstream financial support.

Among the opposition, NUP has stood out for launching a public fundraising campaign. Muguzi praises the initiative, calling it the right step in the face of adversity: “That is what political parties should do. It’s time to go out and mobilize resources.”

However, Muguzi warns that the scale of funding required to mount a competitive national campaign is astronomical.

“To have a fair shake in the arena, a party like NUP needs upwards of half a trillion shillings. Ten or twenty billion shillings is simply not enough.”

This leaves parties with few options — either continue raising funds publicly, despite the risks, or find alternative paths such as nomination fees.

“There are no legal requirements in Uganda for political parties to disclose the sources of their campaign financing,” Muguzi notes, “which creates a loophole that could be used to secure anonymous support from well-wishers.”

Another challenge, Muguzi points out, is the culture around political support in Uganda.

“Many supporters expect to receive from the party, rather than contribute to it. This is a distortion of what democracy should be.”

According to him, a political party worth its name should have two categories of supporters: registered members who pay fees, and committed individuals who raise money for the party.

“Unfortunately, many parties have been lazy about fundraising,” he says. “Yet the strength of a party lies in the size of its war chest.”

Looking ahead, Muguzi warns that the 2026 general election could be the most expensive Uganda has ever seen.

With more urban centers now established — over ten cities compared to just one in the past — competition is expected to be fiercest in these areas, where opposition parties typically have a strong foothold.

And then there’s the electorate itself.

“The electorate has been wired to think of elections as a time to harvest,” Muguzi says.

“Candidates are going to meet a hungry, thirsty electorate that will demand more than ever before.”

As the campaigns gather momentum, it remains to be seen how opposition parties will navigate the tough terrain of political financing.

But one thing is certain: in Uganda’s evolving political landscape, fundraising is no longer optional — it is a lifeline.