Are Uganda's political parties pathways to progress or chains of control?

Political parties in Uganda ostensibly are among the many vehicles for reform and democratic progress.

However, their internal dynamics and workings often reveal a different reality, where control mechanisms suppress party initiatives. This dual nature raises the question of whether Uganda's political parties chains of control or pathways to progress?

The nature of opposition outside political parties is characterised by among others, individual and collective movements that many a times, their structures are not aptly streamlined, unpredictable, difficult to control or predict which informs their registered degree of their effectiveness.

The journey of movements in Uganda in itself dates from most recently the People Power movement, which emerged in the mid-2010s and gained significance in 2019, to earlier movements like Togikwatako, which opposed the amendment of the Ugandan constitution to remove the age limit for the presidency.

Before that was People's Government, established in 2018 by Dr. Kizza Besigye and his supporters after the disputed 2016 elections, the list goes on.

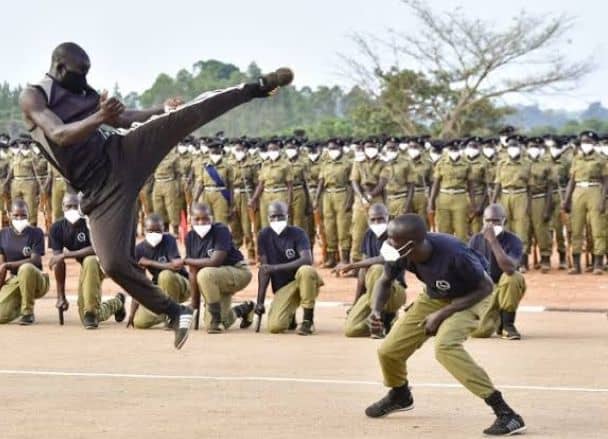

Movements like A4C (4GC, For God and My Country) and People Power thrive on grassroots energy, street protests, and digital savvy. Led by impassioned youth, they defy authority through civil disobedience and social media mobilization.

With fluid leadership and decentralized structures, they adapt quickly and challenge the status quo head-on, embodying a radical and unpredictable force for change in Uganda.

In this very landscape, individuals like Bobi Wine have also managed to wield significant influence by mobilizing mass support and challenging the status quo. However, sustained change relies on broader factors beyond just individual leadership.

With the ruling party, National Resistance Movement (NRM), political analyst Yusuf Sserunkuma aptly describes it, as more akin to a monarchy than a political entity, with power centralized around President Museveni himself.

He adds that Museveni's astute manipulation of financial resources, effectively 'buying off' political parties, has further weakened the opposition's resolve.

The demise of once-prominent parties like UPC, DP, and FDC, along with the recent struggles of NUP, illustrates Museveni's mastery in maintaining control, as observed by Yusuf Sserunkuma.

"The current state of political parties in Uganda completely aligns with Museveni's vision – fragmented, disorganized, and embroiled in internal strife."

This dysfunctionality not only undermines the credibility of opposition movements but also strengthens Museveni's grip on power.

Sserunkuma's sobering analysis highlights the paradoxical nature of Ugandan politics: even the most well-intentioned individuals risk succumbing to corruption within the system.

Yet, amidst this bleak landscape, voices of opposition and citizen activism continue to challenge institutional corruption and demand accountability.

As citizens awaken to the realities of their political landscape, the seeds of change are sown, offering a glimmer of hope for a more transparent and equitable future.

The question to ponder, then, is whether these advocates for change can benefit from engaging with political parties, or if they are better off operating outside these institutions.