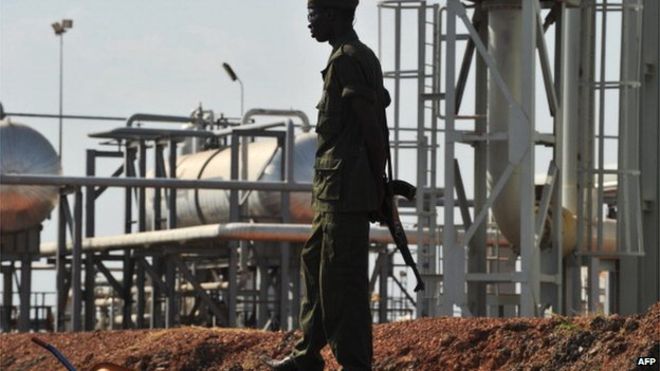

2019: There is hope for South Sudan’s oil industry

South Sudan’s long-suffering oil industry is looking with fresh optimism at 2019 following the East African producer’s latest peace deal which promises to reenergise the sector after years of bloody civil conflict.

The oil industry has already seen some recovery following the peace pact signed by President Salva Kiir and rebel faction leader Riek Machar in the Sudanese capital Khartoum in September 2018.

Keep Reading

The deal has ushered in new opportunities, prompting South Sudan’s Unity oilfields that were shut since January 2014 to restart pumping 20,000 b/d of crude oil.

At their peak, the Unity oilfields, located on the border with Sudan, used to produce 45,000 b/d of Nile Blend crude, a light, sweet but waxy crude oil that is popular among Asian refiners.

Contracts were extended under the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company, or GNPOC, which operates the block and includes India’s ONGC Videsh, Malaysia’s Petronas, CNPC of China and Nilepet of South Sudan.

“These are the fruits of the peace that have been achieved in South Sudan. The people of South Sudan should uphold this peace and promote the spirit of peaceful co-existence,” Sudan’s head of National Security, Salah Gosh, was quoted as saying by local media during a visit to the Unity oilfields last month.

The full resumption of oil production in blocks 1, 2, 4 and 5A would enable South Sudan to “gain a reputation as a leading oil producer,” oil minister Ezekiel Lol Gatkuoth said at the time.

Neighboring oil blocks A1, A2, A3, A4 and A6 in central South Sudan, close to the northern border, are still open for investors.

Restarting the Unity oilfields and bringing on board new investors have given Gatkuoth the hope that South Sudan should be able to increase oil production to more than 400,000 b/d in 2019. South Sudan’s current output stands at 155,000 b/d of crude oil.

South Sudan, the world’s newest nation after its 2011 spit from Sudan, has a proven reserve of 3.5 billion barrels of oil, the fifth largest reserve in Africa.

New Investors

So far, only Asian investors — Chinese, Malaysian and Indian firms — dominate the country’s oil industry. But giant Russian oil firms such as Zarubezhneft, Gazprom Neft and Rosneft have expressed interests to invest in South Sudan.

Last year Nigeria’s Oranto acquired operating license to explore oil in Block B3, where it has committed $500 million to develop a 24,415-square-kilometer area.

The unexpected new boy on the block is South Africa, which has come on board with a pledge of $1 billion to develop South Sudan’s oil industry. South African Minister of Petroleum and Energy Jeff Radebe held talks with President Kiir at the State House in Juba on November 23.

Gatkuoth said South Sudan and South Africa signed a memorandum of understanding to explore oil and construct a refinery with a capacity to process 60,000 b/d at Palouch, northeast of the country.

Radebe pledged his government’s commitment to ensure the projects signed between the two countries will be implemented. Gatkuoth believes the refinery would feed Ethiopia’s huge market of more than 100 million people.

The peace deal came too late, however, for France’s Total and the UK’s Tullow Oil. The oil majors pulled out of long-running talks for a new production sharing contract on the B1 and B2 oil blocks in July.

Protection Force

Two factors seem to be driving South Sudan’s determination to increase oil output. First, the economy, which relies heavily on oil revenue for 97% of the government annual budget and is badly hurt by the five-year conflict.

This has affected the payment of salaries of government employees.

Sometimes salaries have been delayed for up to three months in a country where year-on-year inflation rate, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, stands at 161.2% as of March 2018, the highest in East Africa.

Secondly, the country’s important northern neighbour, Sudan, which is desperate to keep South Sudan’s oil flowing through its vast territory to the international market.

Khartoum lost most of its oil revenue after South Sudan broke away from the Sudan in July 2011.

To make up for the loss, Juba agreed to remit $1.42 billion in 2014, $1.40 billion in 2015 and $1.11 billion in 2016 to Khartoum for allowing South Sudan’s crude to pass through its facilities near Port Sudan on the Red Sea for export, according to an IMF report in November 2013. Unfortunately, the 2013-2018 conflict affected the remittances.

Before the country’s breakup, the united Sudan used to produce 500,000 b/d of crude oil.

In a bid to guarantee uninterrupted production, South Sudan and Sudan have agreed to deploy a joint oil protection force in the oilfields.

The idea is to prevent a rebel shut down of oilfields as they did to Unity oilfields in January 2014.

To demonstrate Khartoum’s commitment, Sudan oil minister Azhari Abdul-Gadir Abdalla joined his South Sudanese counterpart, Gatkuoth, on a tour of the Unity oilfields in November 2018 and assessed preparations for the resumption of production in the remaining wells there.

These moves will help but similar peace efforts have failed to stick in the past and Juba will need to show lasting progress if it wants to attract a fresh round of investment in the country.

Source: Platts