Part I: How a Ugandan became an American police shooting statistic

On what would be the last day of his life, Alfred Olango showed up at his sister’s apartment in El Cajon, California, in the morning hours. His knocking woke her up.

Alfred was acting strangely – confused, paranoid – and said he hadn’t slept for two days. Lucy Olango, an aide in a psychiatric facility, recognized signs of a mental breakdown.

So she called the 911 emergency number to report that Alfred was mentally unstable and needed hospitalization. It was the first of three such calls she made, pleading for help.

More than an hour later, El Cajon police did respond, although not with the help Lucy expected. As she watched in horror, Alfred was shot four times during a tense encounter with officers. Although he was unarmed, he made a gesture that looked as though he was pointing a gun.

The death of Alfred Olango, 38, on Sept. 27, 2016, was among several captured on video in a year when anger over U.S. police shootings, particularly of black men, rose to new heights.

But his case stood out: His status as a Ugandan refugee brought international attention not only to the issue of race, but to how police react to people with psychiatric problems – a factor in about 25 percent of all fatal civilian encounters with police.

For those reasons, VOA and NBS-TV in Kampala teamed up to more closely examine what happened after Lucy Olango called for help – and whether the shooting could have been prevented.

Our finding: Although Alfred Olango took actions that put him at risk, the system designed to defuse encounters between police and the mentally disturbed also failed him.

A special police team to respond to mental health calls was on duty that day in El Cajon. Previously, local authorities said the two-person Psychiatric Emergency Response Team (PERT) was busy elsewhere and unavailable to respond to Lucy Olango’s calls.

But in answer to a public records request from VOA and NBS, the city of El Cajon released documents – summaries of 911 call records – showing that, in fact, the PERT unit did become available. Although Lucy Olango waited nearly an hour for help, the special psychiatric team was sent to a possible trespass at a youth club.

The summaries for the youth club call make no mention of a mental health issue and the situation resolved without an incident report.

Meanwhile, the Olango call ended in tragedy – one of 963 police shooting fatalities in the U.S. during 2016, according to a count by The Washington Post. (There were 987 such incidents in 2017, according the Post's statistics.)

The local district attorney ruled that El Cajon police Officer Richard Gonsalves was justified in using deadly force when Alfred Olango pointed a vape pipe – for electronic smoking – at him during the encounter. Officials said Olango took what looked like a shooting stance.

But Lucy Olango, Alfred Olango’s estranged wife and two of his three children, and his father have sued the city and Gonsalves, claiming emotional distress and violations of Olango’s civil rights.

Now, the 911 call summaries reveal a new element in the tragedy – a missed opportunity for the unit trained for such incidents to intervene.

“This was a big mistake not sending that PERT team to this (Olango) call because they had every evidence needed that this was the call that required the PERT team,” said Daniel Gilleon, the attorney representing Lucy Olango.

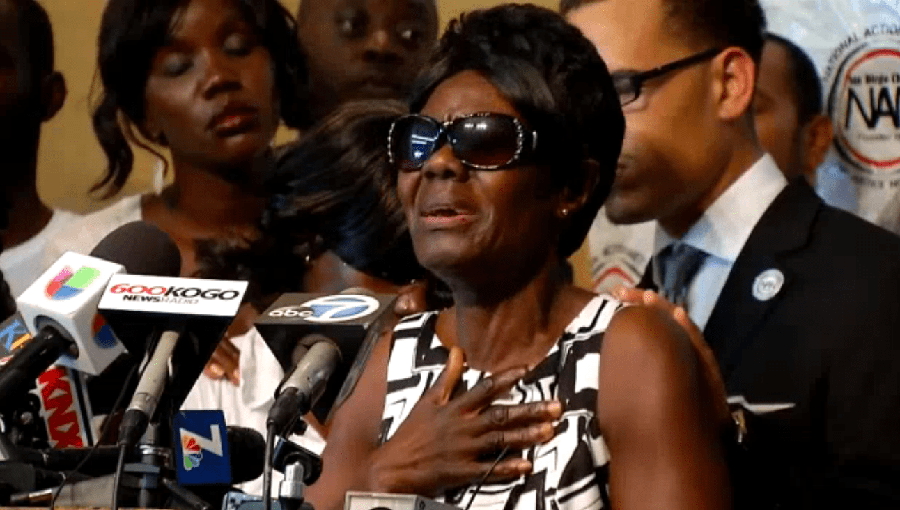

Lucy Olango said Gonsalves used an aggressive approach that only increased the tension with her brother when de-escalation tactics could have helped to calm him down.

“Pulling your gun and saying ‘Put your hands up’ is not a way you come at a person who is having a mental breakdown,” Lucy told VOA and NBS.

“You haven’t even engaged in with this person. You did not find out what was wrong. Can I help you? What is wrong? Is there something that I can do?” she said.

From northern Uganda to US

Alfred Olango was born in Lukutu Village in northern Uganda in 1978, a middle child among nine in his family.