BEECHAM OKWERE

Legitimately December 19, 2016, should have been Joseph Kabila’s last day in office as president of the Democratic Republic of Congo in the country’s first democratic transfer of power since independence in 1960.

The next day, after he refused to step down, at least 34 protestors were killed by security forces.

On December 26, civilians were killed in a massacre in the restive North Kivu province in the east, raising fears that the crisis could lead to further deterioration of the security situation.

However external engagement in the chaotic, violent, and fraud-ridden 2011 elections was minimal. …

The current crisis is a legacy of the 2011 process which seems not to end.

Be that it may in the face of concerns about wider violence and instability as a result of Kabila’s refusal to leave office, the DRC Conference of Catholic Bishops brokered an agreement on New Year’s Eve to establish a transitional government headed by a prime minister to be appointed by the opposition.

Under the deal, Kabila would stay on as president until the end of 2017.

He would not be allowed to run for a third term. The agreement also restores the prime minister with the powers granted to the office in the 2006 Constitution—a significant check on presidential authority.

Kabila has not yet signed the agreement, however, and did not mention it in his New Year’s address.

Given the lengths that Kabila has gone to extend his mandate so far, skepticism that he will abide by the agreement remains high.

Indeed, the current prime minister, Samy Badibanga, has publicly rejected the agreement, calling it “unfit for purpose.”

The actions of African and international actors will be central in keeping the parties to their commitments under the new deal.

Past experience has shown that timely and coordinated external engagement has been a moderating influence that has laid the groundwork for negotiated outcomes.

Uncoordinated or detached international involvement, in contrast, has enabled further escalation.

This lesson is all the more vital, given the inherent difficulty in implementing peace agreements in an environment of deep suspicion among the parties.

A Mixed Record of Engagement

The DRC’s multi-party democratic elections in 2006—the first since the authoritarian regime of Mobutu Sese Seko—marked the high point of foreign engagement in the country’s affairs.

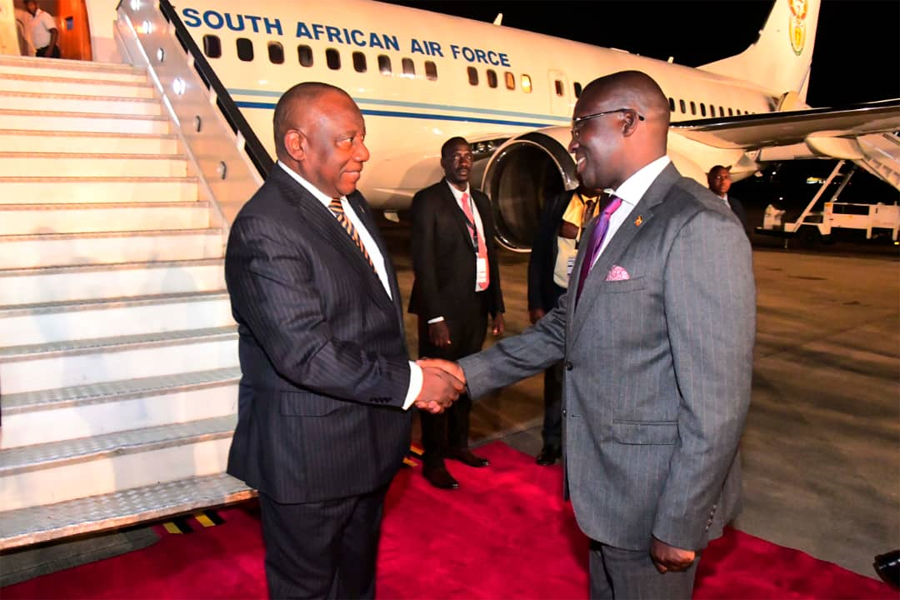

South Africa, as mediator of the Inter-Congolese Dialogue that ushered in a democratic transition after two devastating civil wars, led a robust African effort to create a conducive electoral climate, including lending its electoral equipment to the Congolese election management body.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC), African Union (AU), European Union (EU), and United Nations (UN) worked in a coordinated fashion to support the process.

Key interventions included managing the technical and logistical aspects of the balloting, providing security at polling stations, and mediating election disputes.

By contrast, external engagement in the chaotic, violent, and fraud-ridden 2011 elections was minimal.

According to Congolese scholar Mvemba Dizolele, this “hands-off” and “ad-hoc” approach was driven by a narrow focus on stability and security at the expense of a more sophisticated and long-term focus on stability achieved through inclusive politics as required by Congolese law and by various AU instruments such as its Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance.

The current crisis is a legacy of the 2011 process. In the process, Joseph Kabila’s legitimacy was badly weakened, political consensus has dissipated, and opponents have fled into exile.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC)

SADC’s leverage in the DRC comes from several decades of security engagement and regional diplomacy.

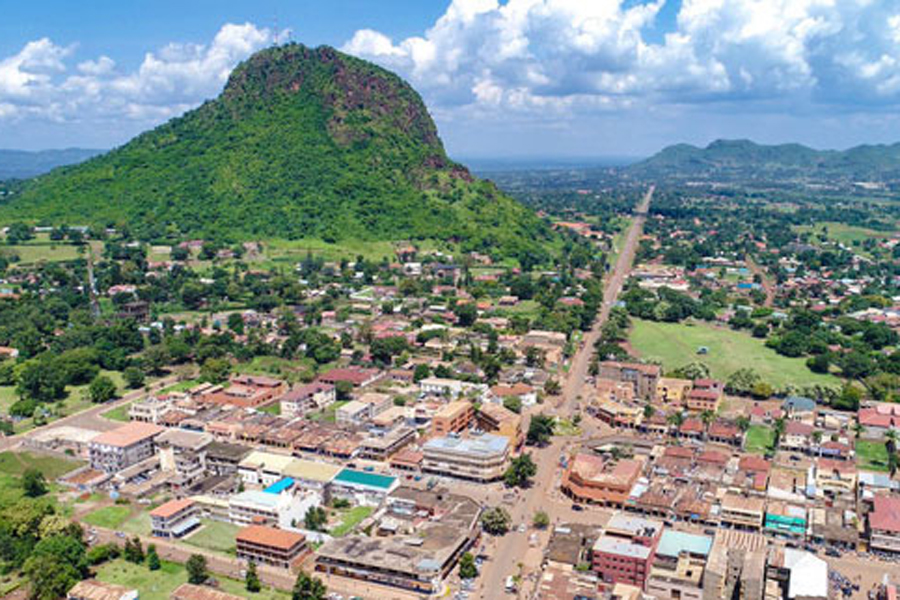

It twice intervened in a stabilising role. The first was in 1998, when it invoked collective security by authorising intervention by Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe to beat back a Rwandan and Ugandan invasion that had reached Kinshasa.

The second was in 2003 when SADC left a residual force to guarantee the country’s defence and build the DRC’s security sector after the war.

In keeping with this commitment, SADC in 2013 deployed the Force Intervention Brigade, consisting of troops from Malawi, South Africa, and Tanzania, to neutralise the M23 rebels in eastern DRC.

SADC’s effectiveness will depend on whether its efforts are employed even-handedly, and in ways that tie SADC’s strong security interest in stability with an inclusive democratic process.

The lessons of African and international engagement in the 2006 elections show that the unity of these efforts can help deliver a democratic outcome.

This can only be replicated if the AU, SADC, IGCLR, UN, and EU work as a team with one voice in engaging the parties.

The role of regional and international actors in mitigating regional conflagration will also be vital given the record of crises spilling over borders in the region.

In 2013 up todate, the AU negotiated a security compact between the DRC and its neighbours including commitments against introducing hostile forces or supporting proxies in the DRC.

This compact should be invoked as the Congolese continue to navigate the current political crisis.

©Beecham Okwere Foundation